How to mute a mic in six months

12 August 2020

by Matt

There's an undeniable appeal in simplicity, especially as technology feels increasingly complex. The products we love the most are often the ones that feel the simplest, even if they aren't necessarily the ones that do the least.

From a consumer perspective, this often creates something of a paradox—when an app feels simple, we think that it must have been simple to build, but often, the inverse is true. Building an app that feels simple for users can often require more work under the hood than it would to build a more complex app, because we're managing that complexity in the code, rather than asking the user to handle that complexity for us.

That's good for users—but not so great for us, when we just wanna ship our damned app! 😅

If I had more time, I'd write a shorter letter

Mic Drop is a macOS menubar app that allows you to mute and unmute your microphone with a keyboard shortcut. The goal of the app is to provide a customisable, easy, and reliable way to control your microphone in remote meetings and calls.

Mic Drop's core functionality—muting the microphone—is simple to describe but complex to implement. It's the perfect example of developer hubris: "Easy. I could build it in a week!" That's what I thought too.

In November. (Note: We released Mic Drop in April.) 😅

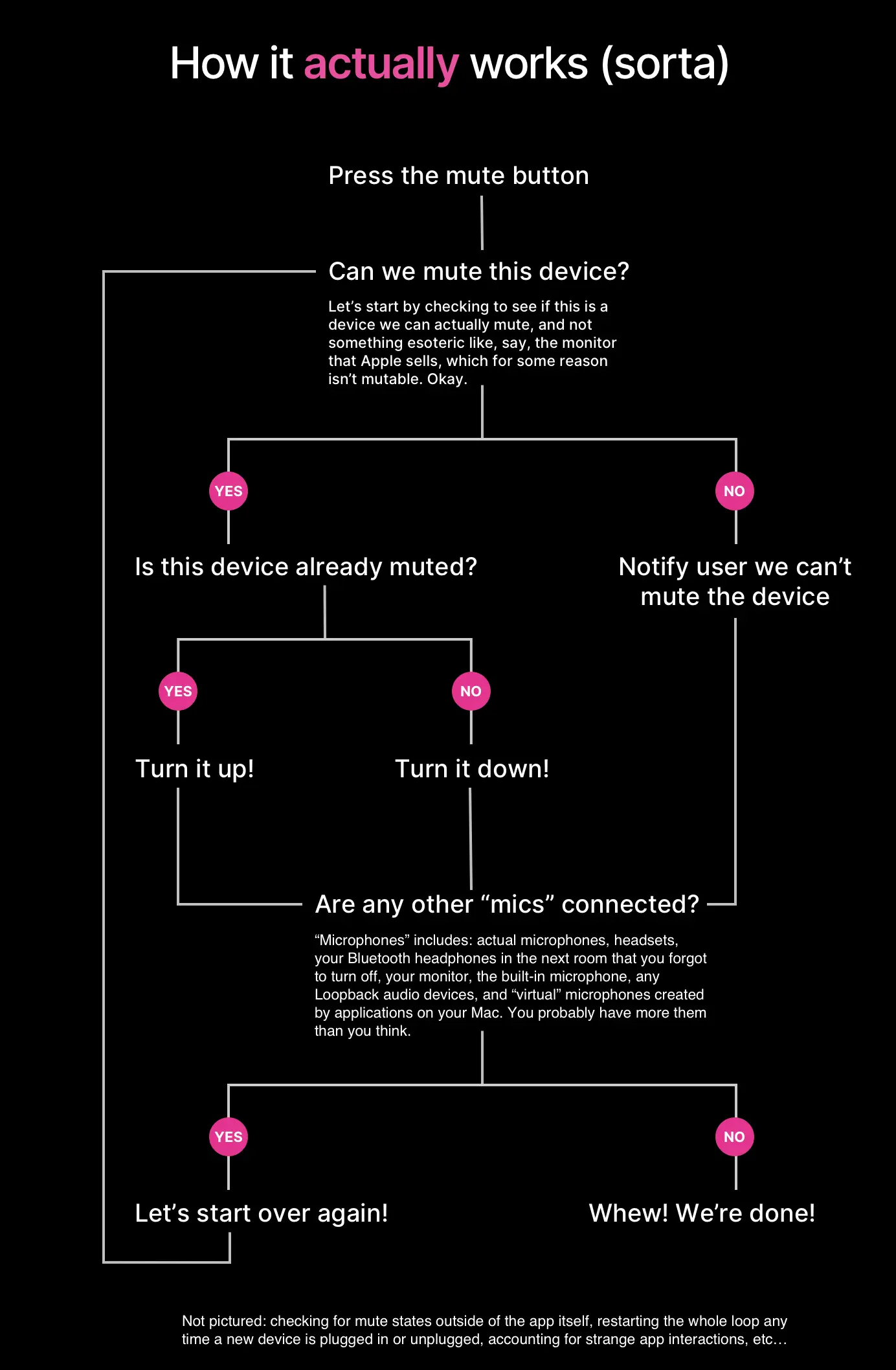

To mute the microphone, Mic Drop relies on macOS's Core Audio framework. It's a set of APIs that controls low-level audio device functionality on Macs. It's been around for a long time, and as a result it's pretty complex and certainly very-edge-case-y.

It turns out managing inputs like microphones is much more complicated than we thought! From aggregate inputs and loopback devices, not every input device is a real microphone. There are microphones that ignore mute settings, and some that claim to honour mute status but don't. (I'm looking at you, LG UltraFine 5K.)

There's a whole lot of code for handling edge cases in Mic Drop!

Let's not reinvent the wheel

We built on top of existing open-source libraries to handle recording keyboard shortcuts. We've shared these customised versions of these libraries so you can use them in your own projects.

We published an Under the Hood page on the Mic Drop website. This is something we'll be doing for all future apps—partly because we're curious, and partly because we're fans of transparency. It allows us an opportunity to explain our choices and gives others a reference for their own projects. 📕

It turns out it's one of the most popular pages on the Mic Drop website, so either people are curious or they're finding it useful. We'll definitely stick with the habit.

On macOS—and the Mac App Store

We're web people at heart, and though we've made iOS and Android apps in the past, this is the first macOS app we've shipped. It's also the first app we sold via the Mac App Store.

At first, we weren't even sure if we would ship Mic Drop to the Mac App Store—but I'm glad we did.

It's frustrating to be paying $99/year and 30% to Apple—a company famed for their excellent user experience—and then have Apple's review process block us from shipping bug fixes to users, sometimes for lengthy periods of time. 😤

I know App Store review times have improved a good deal, but the unnecessary opaqueness of the process and the comparison to the ease of self-publishing updates is a needless frustration.

That said: we can't deny that the Mac App Store has benefitted app sales. This month Mic Drop has made about 50% of its revenue via the App Store, and we get some sales from organic searches via the app store.

Singing to myself

Building an audio app makes for some strange development habits. Sometimes I sing into the microphone with a VU meter open to see if the mute is working.

There was a bug related to a menubar API when multiple monitors were used with a MacBook screen open. Since I have a single-monitor setup at my desk, I had to get creative to reproduce the issue:

So many Vespas! 🛵 (Including on my coffee cup.)

Hardware is hard

Testing meeting software is easy. Most meeting apps have a free version we can test with.

But not all audio hardware behaves consistently, and it's a real pain to diagnose issues without the hardware on hand. A lot of the hardware people write in about is expensive and niche, so it's often quite costly to test an issue for one user. We try really hard to offer great support, but the maths on that is tricky—a £500 device for a £4 sale (of which we're donating £2, and the taxman takes nearly £1) is the kind of business practise that makes our accountant give us long lectures.

I won't lie: we've (ab)used generous return policies a few times, because we don't have much use for a £500+ USB-XLR Audio interface after we've debugged its issues. 😆

Betas are the best

I'd be remiss if I didn't mention some of the awesome and creative users we've met during Mic Drop's early development. ❤️

This was our first Mac app and we're a young company, so our beta group was pretty small. But those users provided really excellent feedback. Even if your beta group is tiny, it's worth doing to get any feedback you can and ensure your app works for people before you ship it to the world!

One of our beta users (hi Enrique! 👋🏻) shared feedback that, after some discussion with Sarah, led to the status window feature. I was skeptical at first, but it's turned out to be a very popular feature. Heck, even I use it now! 🙃

Another user was building an Arduino-powered "On Air" light switch to hook up to a keyboard shortcut for Mic Drop. Pretty cool! (Send photos, please!) 💡

Greener pastures (in defense of the web)

I often hear developers bemoan the amount of technology needed to build even a simple "Hello world" web app. From transpiling ES6 with Babel to managing assets with Webpack: there's a lot to learn to make a good website these days. Gone are the days of "write some HTML, CSS, and maybe some jQuery" to build a website or an HTML app. But it's backward to observe this trend and proclaim: The web is getting too complex because the build systems are complex! The reality is those build systems are evolving at the same rate as the web itself, which can do a lot more than it could it the days of jQuery 1.0.

Venture into Xcode and you'll observe the same sort of complexity. Except it's obscured by an IDE and a lack of open-source code. Say what you will about the web, but you can always go to the source if needed—and with the functional and modular approach more build tools and libraries are taking, you aren't locked into a development paradigm like you were in the days of WordPress or Rails. Conversely, Xcode and the Apple toolchain are pretty much the only way to build a macOS app aside from Electron.

All of this is just to say that the grass is always greener. Xcode can be frustrating, opaque, and restrictive. It comes a steep learning curve. I had plenty of "oh, cool!" moments building Mic Drop, but my frustrations with Xcode were similar to the frustrations I encounter with any new tool. 🤷🏻♂️

Once more unto the breach

After all that: would we do it all over again? We sure would! In fact: we've already started!

We're currently busy working on another menu bar app, except this one will be for both macOS and Windows. It's a timer app, for freelancers and other people who need to track the time they spend working on projects. It's currently especially designed for users of FreeAgent, but we're planning other integrations and a standalone version as well.

If you want to hear more about it sign up for our newsletter (at the bottom of the page) or follow us on Twitter to get notified when we start the beta!

Back to all posts

Unsubscribe any time. We won’t ever share your information with anyone else. Privacy.

Made with and by Sarah and Matt